Acupuncture: A Fusion of Ancient Wisdom and Modern Science

Nationally Licenced Acupuncturist (Japan)

Traditional Chinese Medicine and Kampo Practitioner

June 1, 2023

(Original version of this article was published online on Dec 1, 2018)

Acupuncture, a key component of traditional Chinese medicine, involves the insertion of thin needles into specific points on the body, known as ‘acupoints’. These points may be stimulated by the practitioner through various methods, such as tapping, rotating the needles, or applying heat or electrical stimulation. This technique is believed to balance the flow of energy, or ‘qi’, through the body’s meridians, thereby triggering beneficial responses. While often used to aid in the recovery from injuries and manage pain, acupuncture also serves broader health purposes. It is frequently employed in the treatment of chronic illnesses like migraines and arthritis, utilized as a preventative measure against disease, and valued as a tool for enhancing overall wellness by fostering a balanced energy state within the body. Acupuncture is also gaining recognition for its potential benefits in addressing fertility issues. By promoting a balanced state of health, acupuncture may enhance fertility and support reproductive health. It’s important to highlight that while acupuncture provides a comprehensive approach to health care, treating the body as a whole, it is typically used as a complementary therapy alongside conventional treatments.

The Historical Journey of Acupuncture: From Ancient China to Global Recognition

Acupuncture, first documented over 2,000 years ago in the ancient Chinese medical text “Huang Di Nei Jing” (The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine), has a storied history. Originating from China, this practice spread to Japan and Korea in the 6th century. Before the introduction of allopathic medicine from the West, many Asian countries heavily depended on acupuncture practitioners as their primary healthcare providers. In conjunction with Chinese herbal medicine, acupuncture served as a comprehensive treatment for both acute and chronic illnesses throughout the ages [1].

Acupuncture’s Voyage: Ancient China to Europe

Acupuncture and other ancient Chinese therapeutic practices first found their way to Europe in the 16th century, carried by Italian Jesuit missionaries such as Matteo Ricci, and others returning from China [2,3]. One of the earliest mentions of these practices can be found in the work of Portuguese physician Garcia de Orta’s book ‘Colóquios dos simples e drogas da India‘ (1563) [4].

In the 17th century, a more profound cultural and medical knowledge exchange from China to Europe began to take shape. Michał Piotr Boym, a Polish Jesuit missionary, was a pivotal figure in this exchange [5]. In 1631, Boym joined the Jesuits in Kraków, and after some time in Rome, set out on a voyage to Eastern Asia. Upon arriving in China around 1643, Boym dedicated considerable time to understanding the local culture and studying its flora, fauna, and medicine. His works, “Flora Sinensis” and “Briefve Relation de la Chine,” provided a cursory insight into Chinese medical practices, including acupuncture, helping Europeans gain an initial understanding of Eastern medicine.

Dutch physician Willem ten Rhijne delivered a more direct and detailed account of acupuncture. His tenure at Dejima, a Dutch trading post near Nagasaki, Japan, from 1674 to 1676, exposed him to Kampo, traditional Japanese medicine. Ten Rhijne’s work, “Dissertatio de Arthritide: Mantissa Schematica: De Acupunctura: et Orationes Tres” (1683), is considered the first comprehensive European account of Japanese acupuncture and moxibustion. This unique blend of European medical understanding and Asian therapeutic techniques significantly influenced Europe’s interpretation of acupuncture [6-8].

Nevertheless, European medical circles generally dismissed acupuncture until the mid-20th century. It’s essential to understand that the initial interpretation of acupuncture was deeply influenced by prevalent European medical concepts and perceptions of the East, which continued to evolve and change in the ensuing centuries. This rich history of exchange and adaptation paved the way for the global recognition and practice of acupuncture we observe today.

Acupuncture’s Revival in Modern Europe

The rise of modern scientific medicine caused acupuncture’s popularity in Europe to wane in the 19th century. Nonetheless, a few remained fascinated by this unusual technique and continued to study it. Noteworthy is the work of Polish physician Joseph Domaszewski, who wrote a dissertation on acupuncture in 1830 at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow [9].

The mid-20th century marked a resurgence in interest in acupuncture, fueled by French neurologist George Soulié de Morant’s translations of Chinese medical texts in the 1930s [10,11]. In Poland, this resurgence was manifested through Prof. Zbigniew Garnuszewski’s efforts to popularize medical acupuncture practice in Warsaw and other cities during the 1970s and 1980s.

The 21st century witnessed the integration of acupuncture into numerous European national healthcare systems, including the UK, France, and Germany. Today, acupuncture is widely practiced throughout Europe, reflecting a growing interest in merging traditional and holistic medical practices [12.13].

Acupuncture’s Embrace in North America

Meanwhile, North America also welcomed acupuncture. Sir William Osler, a Canadian physician often referred to as the “Father of Modern Medicine”, documented a successful back pain treatment using acupuncture in his medical textbook, Principles and Practice of Medicine (1912 Edition) [14]. The popularity and recognition of acupuncture in the United States have grown rapidly since the 1970s, primarily due to a New York Times article about its use during President Nixon’s visit to China [15].

The interest deepened when a successful open-heart surgery was performed using only acupuncture as anesthesia [16]. As more studies on the analgesic properties of acupuncture were published in English medical journals, the case for acupuncture as a safe, natural alternative for pain control strengthened. It’s suggested that the mechanisms behind acupuncture analgesia involve complex interactions between the central and peripheral nervous systems [17,18]. Many physiotherapy and pain management clinics now incorporate acupuncture into their rehabilitation programs for patients suffering from motor vehicle injuries (e.g., whiplash) and other musculoskeletal pain conditions.

Acupuncture in the Present Day: A Versatile Tool

In recent years, acupuncture has evolved from a pain management tool to a versatile treatment option for a broad range of health issues, including internal organ disorders, psycho-emotional illnesses, addictions [19], and obesity management [20]. Acupuncture is also increasingly used to complement modern medical treatments such as chemotherapy [21], post-operative pain management [22], and advanced assisted reproductive technologies like in-vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments [23].

Acupuncture services are now offered in various settings beyond medical centers, such as aesthetic salons, anti-aging spas, wellness resorts, and even cruise ships. This is largely due to the rising interest in acupuncture facial revitalization, or cosmetic acupuncture, a technique used to enhance facial appearances [24-26].

The Science Behind Acupuncture

Acupuncture originated with the understanding that twelve primary channels or “meridians,” traverse vertically throughout the body, linking the internal organs. A fundamental principle of acupuncture is the belief that Qi (akin to the Western concept of vitality or life force) flows along these meridian lines. Traditional Asian medicine identifies over 2,000 acupuncture points on the human body, with the World Health Organization presently acknowledging 361 points linked by meridian channels [27]. The chosen points for treatment may be at the location of discomfort or distanced from it. According to traditional Chinese medicine, optimal health necessitates balanced forces within the body. Illnesses, pain, and discomfort emerge when this flow is obstructed or stagnant. Qi stagnation and Blood stasis (old blood stagnation) are two of the most prevalent diagnostic patterns in traditional Chinese medicine. The primary therapeutic aim of traditional acupuncture is to eliminate these blockages and reinstate the appropriate flow within the body.

How is the traditional Chinese medicine concept of “stagnated or blocked flow” interpreted in our modern medical understanding?

Ancient Chinese medicine practitioners and acupuncturists identified the significance of proper flow within our bodies for maintaining good health centuries ago. From a Chinese medicine perspective, the adequate flow of blood (and Qi) is considered paramount for our bodies to operate freely without pain or illness. Sufficient blood flow is also crucial from modern physiological perspectives. Disruptions in blood flow to your major arteries and essential organs can result in severe health implications. Our circulatory system ensures efficient delivery of oxygen and nutrients to organs and tissues and facilitates the removal of metabolic waste. Various organ dysfunctions, skin conditions, hormonal disorders, and symptoms such as easy fatigue, lack of concentration, cold extremities, and susceptibility to injuries are often correlated with inadequate circulation.

Acupuncture and Blood Flow

Acupuncture is well-recognized for enhancing blood flow [28,29]. Experimental studies have shown that acupuncture induces physiological responses both locally (around the needled site) and distally from the stimulation point, including in internal organs. For local blood flow, laboratory experiments suggest that acupuncture stimulation on the body surface excites sensory nerve fibers and triggers an axon reflex (axon refers to a nerve fiber). This reaction releases certain substances like calcitonin gene-related neuropeptide and substance P, causing dilation of blood vessels, resulting in increased local blood flow [30-32]. Enhanced blood flow in the skin and muscle could expedite the elimination of ‘algesic’ (pain-causing) substances. Therefore, one of the mechanisms that reduce pain around the acupuncture site could be due to increased local blood flow following stimulation.

Several human and animal studies have also demonstrated the efficacy of acupuncture on internal organs, notably improving ovarian and uterine blood flow [33-35]. The elicitation of responses distal to the stimulation point, including visceral organs like the uterus or ovaries, are primarily due to physiological reflexes called spinal (segmental) and supraspinal (systemic) reflexes. Regardless of the method of acupuncture administration (targeting a specific nerve, muscle, or traditional acupuncture point along the meridian), localized, segmental, and systemic responses are provoked simultaneously upon needling. It has been established that certain acupuncture techniques induce predominantly local effects, while others evoke mainly systemic reactions. Experienced acupuncturists strategically elicit different physiological responses depending on each patient’s clinical situation. Although acupuncture’s primary principle lies in the belief that the meridian system — the flow of energy, or Qi — permeates the entire body, the new scientific knowledge gleaned through research is integrated into classical acupuncture concepts for optimal clinical outcomes. Whether in Japan, Europe, or elsewhere, the practice of acupuncture is a blend of traditional wisdom and modern understanding.

Exploring the Health Benefits of Acupuncture

Although acupuncture has traditionally been used primarily for pain management, it offers an array of additional health benefits. Apart from enhancing blood flow as previously outlined, research demonstrates that acupuncture can modulate immune function [36] and the autonomic nervous system [37,38]. Over the past few decades, various randomized clinical trials have been conducted, investigating the effectiveness of acupuncture in treating a broad spectrum of health conditions. In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) released a comprehensive review report titled ‘Acupuncture: Review and Analysis of Reports on Controlled Clinical Trials’ [39]. This report, based on an analysis of various clinical trials, highlights 28 health conditions that acupuncture can potentially treat. These include ailments such as allergic rhinitis, depression, dysmenorrhea (painful menstrual periods), headache, knee pain, low back pain, neck pain, and sciatica. More rigorously conducted systematic review and meta-analysis studies, surpassing the WHO review, provide evidence that acupuncture can significantly improve conditions such as low back pain [40], migraine prevention [41], osteoarthritis [42], and post-operative nausea [43].

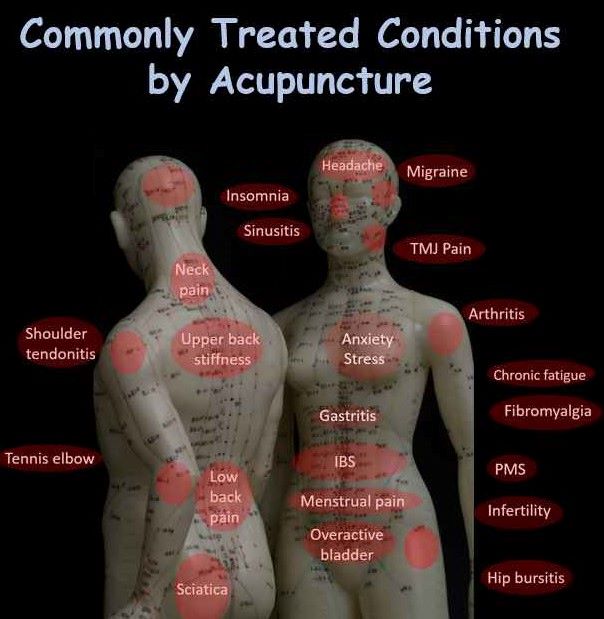

Common Health Conditions Treated by Acupuncture

Acupuncture is commonly used to treat a variety of aches, pains, and muscle/joint stiffness issues. These include headaches, low back pain, neck pain, sciatica, sports injuries, TMJ (jaw pain), fibromyalgia, and more. It is also used to address emotional disorders and stress-related conditions such as depression, anxiety, insomnia, among others. Digestive problems, including gastritis, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), constipation, bloating, are also treatable through acupuncture. It’s been found effective in handling bladder urinary problems such as recurrent urinary tract infections, overactive bladder, etc. Acupuncture can be beneficial for female health and fertility concerns such as irregular menstruation, dysmenorrhea (painful periods), polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), and infertility issues (unexplained infertility, IVF assist acupuncture, recurrent miscarriages, etc.). Finally, acupuncture is utilized for treating other health issues such as allergy-related symptoms, acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis (eczema), chronic fatigue, post-concussion symptoms, etc.

Moxibustion: An Ancient Complement to Acupuncture

Moxibustion, a modality of acupuncture practice, is a form of thermal therapy involving the burning of the moxa herb over specific acupuncture points. The word “moxibustion” is derived from the Japanese term “mogusa,” meaning the moxa herb (Artemisia Princeps, often referred to as Japanese mugwort), and the Latin term “bustion,” which denotes burning. Moxibustion therapy has been used alongside traditional acupuncture for the treatment and prevention of various illnesses in East Asia since ancient times.[1]

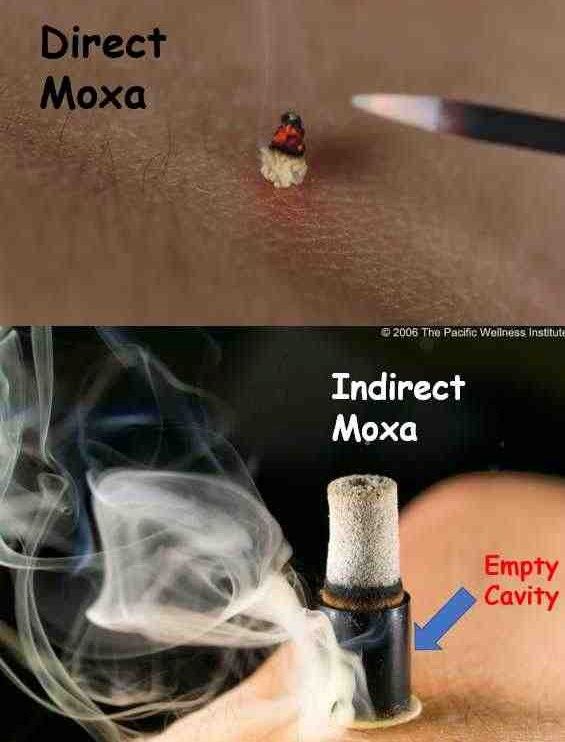

Different Types of Moxibustion

Moxibustion is administered to acupuncture points using either direct or indirect methods. In recent years, particularly in Western countries, indirect moxibustion, which provides thermal stimulation without direct contact between the burning moxa and the skin, has become more prevalent. There are various forms of indirect moxibustion. One such form is the cylindrical type, which contains dried moxa leaves within a small tube, generating a consistent thermal intensity. Another common type is the handheld moxa-stick. This allows the intensity and dosage of thermal stimulation to be individually adjusted based on each patient’s skin sensitivity.

Moxibustion has been a fundamental component of traditional acupuncture concepts. While many people have undergone acupuncture treatment, fewer have experienced moxibustion. This is partly due to the focus of many brief acupuncture training programs in Poland and elsewhere in Europe on the needling aspect, with less emphasis on in-depth moxibustion training.

The Impact of Moxibustion

Studies suggest that moxibustion stimulation enhances blood flow [44], increases skin temperature [45], and modulates gastrointestinal motility [46]. Moxibustion is a crucial treatment for patients suffering from hie syndrome (cold sensitivity – a health constitution concept in traditional Asian medicine) [47]. This syndrome is common among individuals living in cold climates, such as northern Europe.

Many people who experience stress, low energy, poor digestion, fertility issues, and various other chronic illnesses often exhibit symptoms like cold hands and feet, even during summertime. These individuals frequently have compromised blood flow to their soft tissues and internal organs. The heat stimulation applied to selected acupuncture points increases blood circulation to these organs and induces a deep relaxation response, aiding stress management.

Moxibustion vs. Heating Pad

Moxibustion is different from other heat therapies such as heat lamps, heating pads, or hot stone massages. Indirect moxibustion delivers mild, soothing heat to specific acupuncture points, heating an area smaller than an inch in diameter, while heat lamps and heating pads warm up a broader body area. Moreover, moxibustion doesn’t induce sweating or raise your core body temperature, unlike saunas or hot tubs.

Therefore, moxibustion on selected acupoints can be applied safely and effectively for individuals with hie syndrome, those with a wide range of health conditions, and most pregnant women.

The Power of “Acupuncture Moxibustion”

Acupuncture literally translates to needle-puncture, while moxibustion refers to a form of heat therapy on acupoints. In countries such as Japan and China, the practice is known as shinkyu (or zhenjiu in Chinese), meaning AcupunctureMoxibustion (one word). It is traditionally believed that combining acupuncture with moxibustion significantly enhances the effects of each modality.

Scientific studies show that acupuncture and moxibustion function in distinct ways. While acupuncture primarily induces a physiological response through the nervous system, moxibustion is thought to act more directly on your circulatory or immune systems. A physiological response, known as a neuroeffector response, occurs through mechanisms such as central sensitization, peripheral sensitization, and the axon reflex. These response mechanisms can be triggered by both mechanical and thermal stimulations [48].

Stimulating an acupuncture point using both acupuncture and moxibustion can simultaneously engage different receptors, potentially enhancing the effects of each modality. For certain clinical situations, combining acupuncture and moxibustion may be crucial to achieve optimal outcomes.

References:

1. Needham J, Lu G. Celestial lancets: a history and rationale of acupuncture and moxa. Cambridge University Press, 1980.

2. Giovanardi CM, Mazzanti U, Poini A. Acupuncture in Italy: state of the art. Integr Med Res 2020;9:1-4.

3. Bivins R. Expectations and expertise: early British responses to Chinese medicine. Hist Sci 1999;37:459-89.

4. Pelner L. Garcia da Orta pioneer in tropical medicine and botany. JAMA 1966;197:996-8.

5. Mungello DE. Curious land: Jesuit accommodation and the origins of Sinology. University of Hawaii Press, 1989:139.

6. RHIJNE Wt. Dissertatio de arthritide: Mantissa schematica: De acupunctura: et orationes tres. R. Chiswell, 1683.

7. Tan WYW. Rediscovering Willem ten Rhijne’s De Acupunctura: the transformation of Chinese acupuncture in Japan. In: Translation at work. 108-33.

8. Cook HJ. Translating what works: the medicine of East Asia: in matters of exchange. Yale University Press, 2007:339-77.

9. Kalmus M. Regulation of Chinese medicine in Poland. Longhua Chinese Medicine 2021;4.

10. Dubois JC. Revisiting the medical work of George Soulié De Morant. Chin Med Cult 2019;2:53-6.

11. Candelise L. George Soulié de Morant: le premier expert Français en acupuncture. Rev Synth 2010;131:373-99.

12. Eardley S, Bishop FL, Prescott P, et al. A systematic literature review of complementary and alternative medicine prevalence in EU. Forsch Komplementmed 2012;19(Suppl 2):18-28.

13. Kemppainen LM, Kemppainen TT, Reippainen JA, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Europe: health-related and sociodemographic determinants. Scand J Public Health 2018;46:448-55.

14. Osler W. The principles and practice of medicine. Appleton & Co., 1912.

15. Reston J. Now about my operation in Peking. New York Times, 1971.

16. Cheng TO. Acupuncture anaesthesia for open heart surgery. Heart 2000;83:256.

17. Stux G, Hammerschlag R. Clinical acupuncture: scientific basis. Springer, 2001.

18. Pomeranz B. Scientific basis of acupuncture. In: Acupuncture textbook and atlas. Springer-Verlag, 1987:1-34.

19. Moner S. Acupuncture and addiction treatment journal. J Addict Dis 1996;15:79-100.

20. Cho SH, Lee JS, Thabane L, et al. Acupuncture for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes 2009;33:183–96.

21. Ezzo J, Streitberger K, Schneider A. Cochrane systematic reviews examine P6 acupuncture-point stimulation for nausea and vomiting. J Altern Complement Med 2006;12:5.

22. Sun Y, Gan TJ, Dubose JW, et al. Acupuncture and related techniques for postoperative pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BJA 2008;101:151–60.

23. Zheng CH, Zhang MM, Huang GY, et al. The role of acupuncture in assisted reproductive technology. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012;2012:543924.

24. Caulfield T. Is Gwyneth Paltrow wrong about everything? When celebrity culture and science clash. Viking, 2015.

25. Donoyama N, Kojima A, Suoh S, et al. Cosmetic acupuncture to enhance facial skin appearance: a preliminary study. Acupunct Med 2012;30:152-3.

26. Yun Y, Kim S, Kim M, et al. Effect of facial cosmetic acupuncture on facial elasticity: an open-label, single-arm pilot study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:424313.

27. World Health Organization. Standard acupuncture nomenclature. 2nd ed. 1993.

28. Mori H, Kuge H, Tanaka TH, et al. Influence of different durations of electroacupuncture stimulation on skin blood flow and muscle blood volume. Acupunct Med 2014;32:167-71.

29. Mori H, Kuge H, Watanabe M, et al. Does electroacupuncture influence skin temperature, skin blood flow, and muscle blood volume among stimulation sites? Med Acupunct 2016;28:325-30.

30. Sato A, Sato Y, Shimura M, et al. Calcitonin gene-related peptide produces skeletal muscle vasodilation following antidromic stimulation of unmyelinated afferents in the dorsal root in rats. Neurosci Lett 2000;283:137-40.

31. Kashiba H, Ueda Y. Acupuncture to the skin induces release of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide from peripheral terminals of primary sensory neurons in the rat. Am J Chin Med 1991;19:189-97.

32. Jansen G, Lundeberg T, Kjartansson J, et al. Acupuncture and sensory neuropeptides increase cutaneous blood flow in rats. Neurosci Lett 1989;97:305-9.

33. Uchida S, et al. Ovarian Blood Flow is Reflexively Regulated by Mechanical Afferent Stimulation of a Hindlimb in Nonpregnant Anesthetized Rats. Auton Neurosci 2003;106:91-7.

34. Hotta H, et al. Uterine Contractility and Blood Flow are Reflexively Regulated by Cutaneous Afferent Stimulation in Anesthetized Rats. J Auton Nerv Syst 1999;75:23-31.

35. Stener-Victorin E, et al. Reduction of Blood Flow Impedance in the Uterine Arteries of Infertile Women with Electro-Acupuncture. Hum Reprod 1996;11:1314-7.

36. Mori H, Tanaka TH, Kuge H, et al. Effects of acupuncture treatment on natural killer cell activity, pulse rate, and pain reduction for older adults: an uncontrolled, observational study. J Integr Med 2013;11:101-5.

37. Mori H, Tanaka TH, Kuge H, et al. Is there any difference in human pupillary reaction when different acupuncture points are stimulated? Acupuncture Med 2010;28:21-4.

38. Tanaka TH, Leisman G, Nishijo K. The Physiological Responses Induced by Superficial Acupuncture: A Comparative Study on Acupuncture Stimulation During Exhalation Phase and Continuous Stimulation. Int J Neurosci 1997;90:45-58.

39. World Health Organization. Essential Drugs and Medicines Policy. WHO, 2002.

40. Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:493-505.

41. Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(6):CD001218.

42. Manyanga T, Froese M, Zarychanski R, et al. Pain management with acupuncture in osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:312.

43. Lee A, Chan SK, Fan LT. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point PC6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;(11):CD003281.

44. Huang T, Wang RH, Huang X, et al. Comparison of the effects of traditional box-moxibustion and eletrothermal Bian-stone moxibustion on volume of blood flow in the skin. J Tradit Chin Med 2011;31:44-5.

45. Mori H, Tanaka TH, Kuge H, et al. Is there a difference between the effects of one-point and three-point indirect moxibustion stimulation on skin temperature changes of the posterior trunk surface? Acupuncture Med 2012;30:27-31.

46. Miyazaki J, Kuge H, Mori H, et al. A moxa stimulation on the leg affected the function of stomach via autonomic nerve system and polymodal receptors. Health 2016;8:749-55.

47. Mori H, Kuge H, Sakaguchi S, et al. Determination of symptoms associated with hiesho among young females using hie rating surveys. J Integr Med 2018;16:1.

48. Sato A, Sato Y, Schmidt R. Somatosensory modulation of heart rate and blood pressure. In: Blaustein MP, et al, eds. Reviews of Physiology Biochemistry and Pharmacology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1997:118-27.